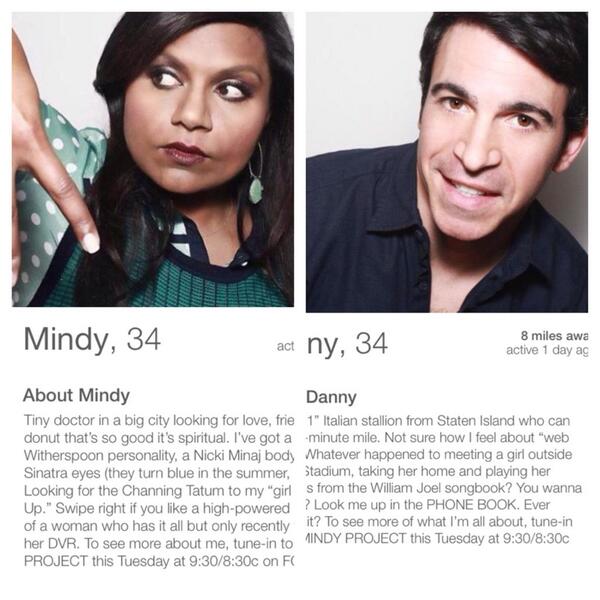

Last January, Fox used the dating app Tinder to promote The Mindy Project via a native advertising campaign which used Tinder profiles of the show’s characters as the creative format.

If an app user ‘matched’ with one of the characters such as Mindy Kaling’s character Dr. Mindy Lahiri, or her obstetrician colleague, the dashing Dr. Danny Castellano, the user received an automated message to ‘tune in to PROJECT this Tuesday’.

The campaign was an exceptionally creative and noteworthy development in native advertising.

The mechanic used was a fit with the dating exploits of the main character, and the ad flowed so seamlessly within Tinder that it was difficult to even recognize it was an advertisement.

The campaign’s tactics are reminiscent of catfishing, the act of pretending to be someone you’re not online to attract another into an online romantic relationship.

The term was introduced to American popular culture in the 2010 documentary Catfish. The film told the story of a shy, New York photographer who thought he met the love of his life, Megan, a beautiful model, painter, dancer, amateur musician and veterinarian’s assistant.

‘Megan’ was in reality a middle-aged, undistinguished and married mother of two. The phenomenon isn’t confined to the lonely-hearts of the Catfish MTV reality TV show spin-off.

A catfishing catastrophe occurred in 2013, when University of Notre Dame football fans were shocked that their favourite linebacker, Manti Te’o, was very publicly catfished.

The number of New York singletons seriously disappointed by the Tinder native ad’s reveal and the discovery that they weren’t going to hook up with a celebrity will be low, if not non-existent.

People would have to be fairly naive to think that the shows characters were putting themselves on Tinder.

Moreover, it became fairly obvious that the profile was intended for commercial purposes through the information in characters profiles and the automated message to reinforce the advertising intent.

Native advertising is all about achieving the right balance of seamlessness with sincerity. When an ad isn’t what it purports to be, it risks the relationship brands want to build with consumers.

Most marketers want consumers to fall in love with their brand. Attracting them through teasing and flirtation isn’t a terrible tactic, as long as the relationship is transparent and there’s no over promising. There needs to be full disclosure to consumers.

In attempting to fit the form and function of publishing platforms, there’s a temptation to make the true character of commercial content difficult to decipher.

If brands do not communicate with complete clarity that the content the consumer sees is a commercially-focused, paid-for advertisement, rather than the content they expect from the publisher, there’s a strong likelihood that consumers will feel disappointed – even deceived – by the ad, whether this was intentional or not.

No matter if it looks like an editorial spread, a social media update or a dating profile, an advertisement is still an advertisement with a commercial objective, not true editorial. If that isn’t clear, there’s the potential the campaign will catfish consumers.

The US Interactive Advertising Bureau recognises the importance of being candid with consumers about the presence of ads within content.

Its Native Advertising Playbook states clearly that rather than the industry’s wonks “almost frantically debating whether or not various ad units are native” they should be “focussing on higher levels of discussions such as effectiveness and disclosure”.

Whilst some in the industry are happy to define native advertising as ‘you know it when you see it’, they perhaps miss the truly key concern: consumers may not always know native advertising when they see it.

Intentionally or not consumers do not always know what is genuine third-party editorial and what is unedited, unbalanced and paid-for advertising.

Disclosure isn’t just an ethical issue. It actually improves advertising effectiveness. Anyone who knows digital advertising knows that the strategy of fooling people into consuming marketing messages through deceptive ads generally results in them becoming annoyed rather than engaged with the brand.

Native or not, tactics that bypass consumers’ informed choice about viewing marketing messages are nothing short of spam, and everybody hates spam.

There’s four key tactics to avoid catfishing consumers:

1. Use clear triggers

The native advertising trigger that consumers interact with to launch commercial messages, whether menu bars, images or hyperlinks, must be identifiably of a different ilk to those used for the publishers’ genuine editorial.

Using a distinct colour for such triggers is a simple way to achieve this.

2. Label with logos

The content of the creative should communicate the advertiser’s identity from the time consumers first notice the ad to the point the brand experience ends.

That’s just good advertising sense, however it can be a challenge to achieve this in native advertising.

There can be a conflict between communicating the brand identity and matching the style and personality of the publishers’ platform.

The aim is to be appropriate to the setting, yet still brand specific. Good native ad formats make consumers aware of the specific brand that wants to communicate with them before the ad is even launched – generally by displaying the brand’s logo.

3. Differentiate from editorial

The creative that the consumer chooses to launch should be distinct from editorial.

Many publishers providing native ad products have opted for a text-based approach: ‘Paid Post’, ‘Promoted by’, ‘Sponsored’ or ‘Brand Publisher’.

However, there’s a variety of ways to achieve this distinction, such as launching ad creative within an advertiser branded console.

This difference is essential for the credibility of the publisher as well as transparent advertising.

4. Consumer choice

Ensure consumers avoid mistakenly thinking a native ad is editorial by displaying a signal that their action is going to launch an ad, as well as giving them time to consider whether they really opt-in to doing so.

The signal doesn’t have to be intrusive, just something as agile as the native ad format, such as a small progress bar.

Typically three seconds is long enough for people to consider whether they want to consume the commercial content, or move on to more editorial.

In summary

The key to a successful native ad campaign is not just in its content, aesthetics, delivery or relevance, but also in its transparency.

Brands should adopt ads that integrate unobtrusively into the content experience. However, if consumers don’t immediately recognize ads for what they are, there’s a good possibility that consumers will feel a bit cheated.

Brands must use candour when courting consumers with native advertising.

Comments