These are best resolved by mixing timing, tact, and sincerity in a neatly delivered apology.

However, standard apologies don’t always cut it.

A successful response to an outcry should depend not only on the particular situation faced but on the identity of the apologizing company in the minds of its customers.

A brand with a reputation for audacity should not offer the sort of grovelling apology expected from more conventional companies.

Know your organization’s image – it’s critical to crafting the proper response to a bout of negative public attention.

Most of the problems organizations encounter when attempting to deal with negative social media publicity begin with a lack of preparation.

Whether you’re Vice Magazine or Astra-Zenica, it will pay to have formed an attitude to adversity – if not the response itself – to be applied in the event of a social media disaster.

This will prevent the sort of scrambled response seen from companies like Applebees and HMV, and will ensure a swifter end to damaging criticism.

Know your company’s image

And be honest. Customers confronting an erring company online do so with a slew of pre-formed perceptions and prejudices.

A misdeed by a major bank, such as Wells Fargo, will be judged more harshly than a popular charity’s misstep, so prepare responses and expectations accordingly.

Don’t let them see you sweat

It never pays to panic.

Organizations that delete negative comments during a social media scandal or engage in online bickering with dissatisfied customers do not fare well, historically speaking.

Part of the reason for this is the simple inefficiency of pursuing individual criticisms; more importantly, such behaviour makes the organization in question look defensive and childish, and therefore probably wrong.

It has become a marketing axiom that non-apologies and outright dismissals of public complaints can cause harm to a company taking abuse online.

This is despite the fact that, most of the time, the marketers are correct.

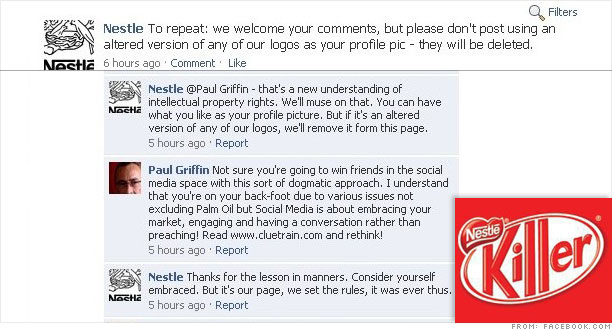

Consider Nestle’s defensive bickering with a Facebook critic or the now-legendary online meltdown of the restauranteurs behind Amy’s Bakery.

In the case of the former, a prickly Nestle employee engaged several Facebook followers in an argument over a request the brand had made of posters to its page, asking that they not use an altered version of the Nestle logo to comment under.

Though probably correct, all this anonymous employee achieved was a disavowal of future patronage by several Nestle customers, and the company was left looking both petty and demanding.

Regardless, some leaders have built brands out of committing PR no-no’s, and it’s important to understand how they’ve accomplished this feat, and why your company may or may not be able to pull it off as well.

In order to classify the wide world of company identities, I’ve created a simple corporate taxonomy; find out where yours lies in this three-part system:

1. The Badgers

The only ones who get to have any fun.

RyanAir and The Onion find themselves here; with an established reputation for surly indifference and good humor, respectively, they seem to get away with a lot.

The benefits of self-reproach are not clear; quick lessons from Steve Jobs and RyanAir CEO Michael O’Leary:

Steve Jobs

Contrition doesn’t suit everybody. True to badger form, the late Jobs was known for his unwillingness to apologize for even substantial Apple mistakes.

On the occasions when Jobs would address a complaint, such as the one following Apple’s rapid $200 price slash of the iPhone (angering buyers who felt they had overspent for their copies of the phone) the press would note the rarity of a Jobs apology.

Confidence in the face of criticism only bolstered the Steve Jobs image, which was – and remains – one of visionary boldness, whilst imparting weight to the few concessions Jobs was willing to make.

Michael O’Leary

As the professional wrestler of the airline industry, the irreverent O’Leary has carved a brand out of foul language and a gleeful disregard for the feelings of RyanAir customers.

Upon reading a dissatisfied customer’s tweet objecting to having been forced to pay £350 for forgetting to print her boarding ticket, O’Leary offered to charge her an extra £60 “for being so stupid.”

He’s a cartoon of the corporate badger type, and yet O’Leary’s eccentric approach to customer relations has come to define RyanAir beyond the bounds of normal corporate stricture, thereby inuring customers to remarks that would (metaphorically) sink a more conventional airline like BA or United.

This may be called the “Donald Trump effect,” and should not be tried at home.

It should, however, be noted that RyanAir has made efforts to reinvent its brand image in recent years, which has led to fewer headline-grabbing comments from Mr O’Leary.

2. The Doves

Not a bad thing to be.

Consumers are generally forgiving of these beloved organizations, and sometimes express disappointment when organizations of this class apologize too quickly.

A version of this mistake occurred when the Red Cross swiftly retracted a poster some Twitter users felt was offensive.

The Red Cross responded with the standard prescription: Apologize and rectify.

The Twitter response to this seemingly sensible move was resoundingly negative.

Most expressed dismay at the knowledge that the Red Cross would be spending donation money to fix what they felt was a non-issue.

Admittedly, the Red Cross was in a tough position in this instance, but by failing to take into account its own good reputation it missed an opportunity to disarm the anti-capitulation crowd with an even-handed response while still placating those that felt the poster was offensive.

3. The Vultures

Not a lovely category, but this is where many mega-companies (like Merrill-Lynch) find themselves.

Unloved and hard to love, the vultures are best off apologizing quickly and doing their best to move on.

Check out BP’s awful apology for the 2010 Gulf Coast Oil Spill.

The archetypical vulture. It repelled its target audience with an over-the-top “we’re sorry” that struck viewers as insincere.

In this case, the public had a clear – and ungenerous – pre-existing view of one of the world’s largest oil companies.

Attempting to persuade the world that BP felt genuine remorse by lavishing production on a YouTube video only exaggerated its image of corporate coldness.

A straightforward, unadorned apology for and acknowledgement of the disaster would not have appeared patronising to the concerned public.

The Takeaway?

Marketers should craft an online persona in line with what customers expect of a company, especially for times of crisis.

There are no hard and fast rules when it comes to crafting a response to a dissatisfied public, but customers generally prefer sincerity over remorse.

Organizations that remember what they are know how much they can get away with (think Steve Jobs) and tend to survive these ordeals with a minimum of dignity lost in the tussle.

Organizations like the Red Cross that forget their good-standing tend to suffer, and the Vultures that never had a good reputation to begin with… well, they do what they can.

Comments